Time Across Civilizations: A Global History of Its Measurement

From the earliest observations of the sky to modern atomic measurement, time has always been an instrument and a reflection of human societies. Each civilization has developed its own methods of measurement and perception of duration, influenced by religion, politics, agriculture, or science.

The first steps: Mesopotamia and Egypt

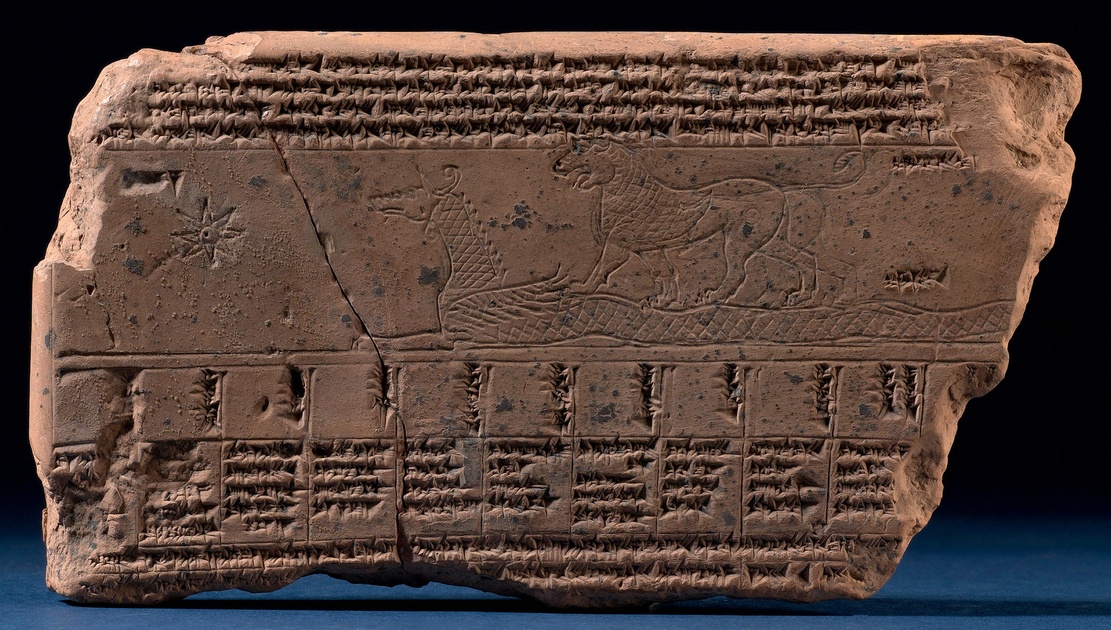

Image: Babylonian astrological tablet

(https://isaw.nyu.edu/exhibitions/babylonian-divination/images/divination-tablet.jpg)

*Credit: ISAW / Public Domain*

In Mesopotamia, the Sumerians and Babylonians observed lunar and solar cycles to regulate agriculture, religious festivals, and civic activities. They invented the sexagesimal system, which remains the basis for the 60 minutes and 360° of the circle.

In Egypt, observation of the Nile imposed a precise 365-day solar calendar. The Egyptians developed sundials and clepsydras (water clocks) to structure the day. These inventions reflected both a practical need and a religious vision of time, in which the rhythm of life should harmonize with the cosmos.

---

The Cosmic Order: China and Mesoamerica

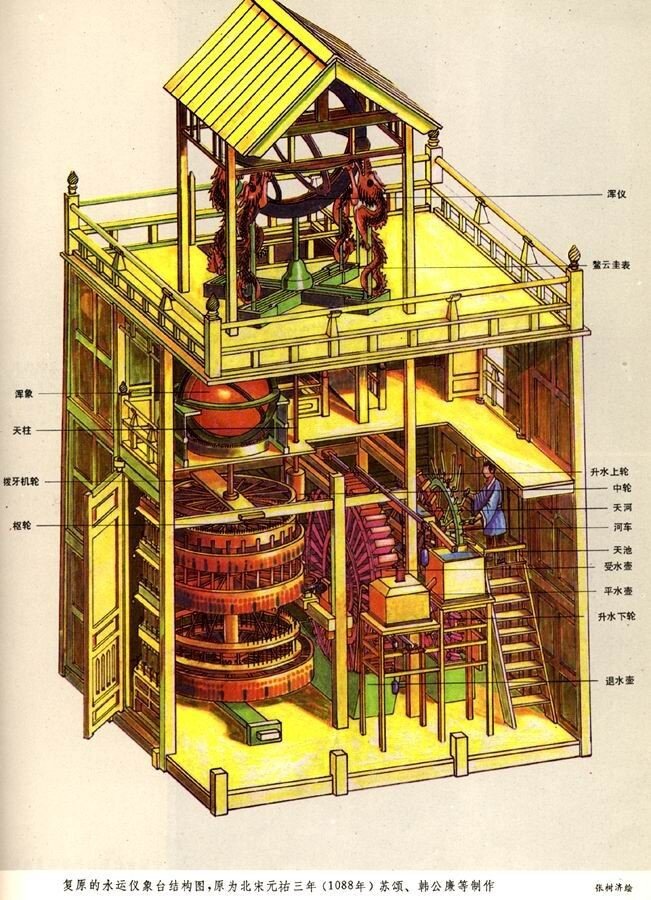

In China, the measurement of time was closely linked to philosophy and astronomy. The lunisolar calendar determined agricultural seasons and festivals. The 11th-century Su Song Clock, a complex chain and waterwheel mechanism, illustrates Chinese engineering genius and the precision of their astronomical instruments.

Image: Su Song's Chain Mechanism (China)

[https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File\:Chain\_drive,\_Su\_Song%27s\_book\_of\_1092.jpg]

The Maya and Aztecs viewed time as a sacred and cosmic cycle. The **Tzolk'in** (260 days) and the **Haab** (365 days) marked the rhythm of agricultural and religious life. The **Long Count** allowed human history to be projected thousands of years into the future, combining astronomical prediction and religious beliefs.

**Image: Aztec Sun Stone (Mesoamerica)**

Credit: National Museum of Anthropology, Mexico City / Public Domain

[https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File\:Aztec\_Sun\_Stone.jpg]

The Maya and Aztecs viewed time as a sacred and cosmic cycle. The **Tzolk'in** (260 days) and the **Haab** (365 days) marked the rhythm of agricultural and religious life. The **Long Count** allowed human history to be projected thousands of years into the future, combining astronomical prediction and religious beliefs.

Science and Power: Greece, Rome and the Islamic World

Image: Arabic astrolabe

Credit: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

[https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File\:Arabic\_astrolabe\_2.jpg]

In Greece, time was both a philosophical concept and a practical tool. Plato and Aristotle pondered its nature, while astronomers perfected gnomons and sundials.

In Rome, the **Julian calendar** (-46 BC) rationalized the measurement of time for administrative management and social organization.

In the medieval Islamic world, time became crucial to religious practice. Astronomers invented astrolabes and hydraulic clocks to precisely determine prayer times and the beginning of lunar months. This knowledge had a strong influence on medieval Europe.

From medieval Europe to modernity

Image: Medieval clock mechanism

Credit: Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-2.0)

[https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Medieval_clock_mechanism.jpg

Mechanical clocks appeared in the 13th century, often in monasteries, then in cities. They helped structure social life, production, and markets. In 1582, the Gregorian calendar corrected the discrepancy accumulated by the Julian calendar and became the standard in Europe.

The Industrial Age: Time as Productivity

*Image: 19th century station clock**

*Credit: Wikimedia Commons / Public domain*[https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File\:Grand\_Central\_Clock.jpg]

*Credit: Wikimedia Commons / Public domain*[https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File\:Grand\_Central\_Clock.jpg]

The Industrial Revolution transformed the perception of time. Factories, trains, and offices imposed strict schedules. Time zones were standardized, and time became linear and synchronous across industrial societies.

Contemporary time: from the atom to instantaneity

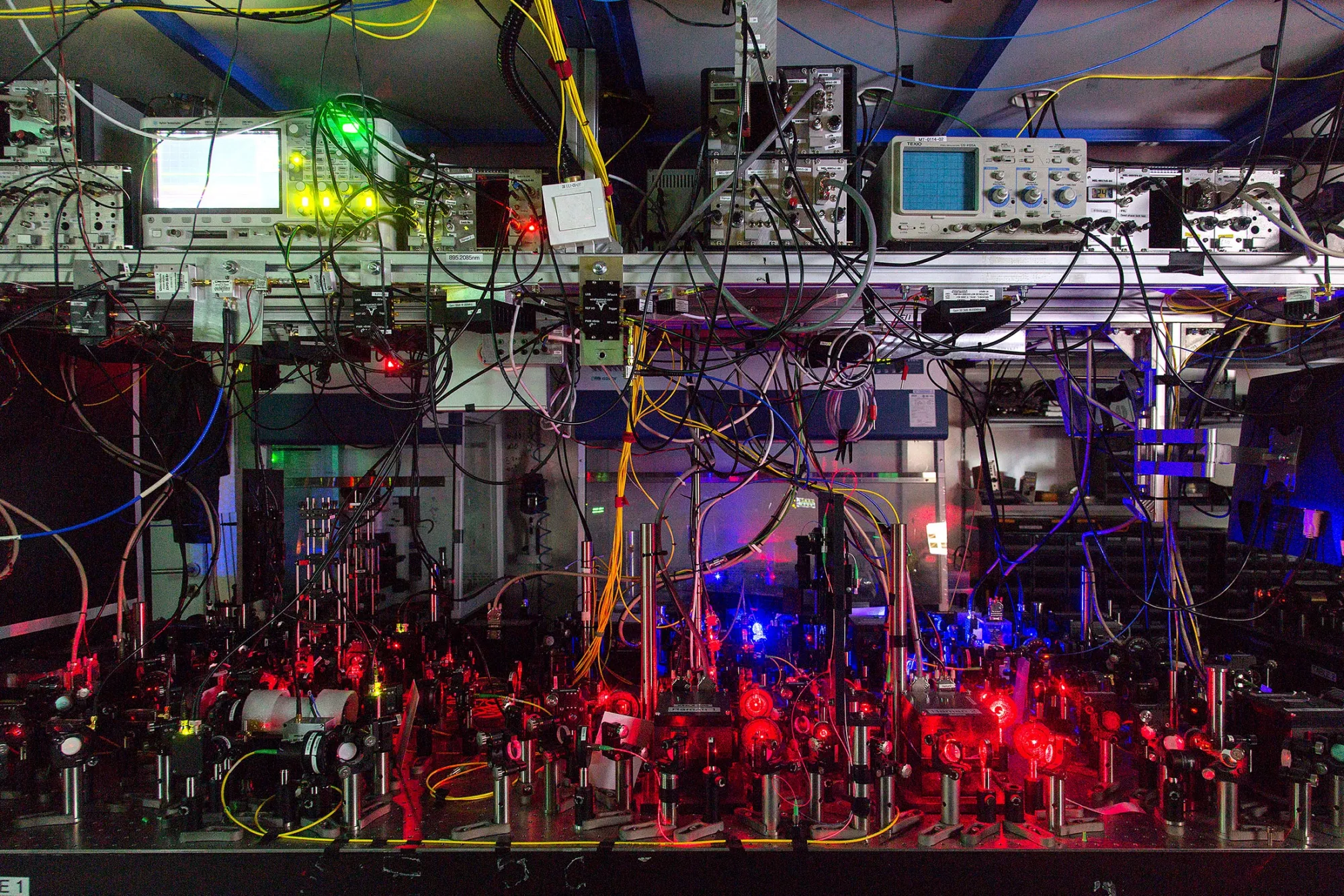

**Image: Atomic Clock**

Credit: NIST / Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain

[https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File\:Atomic\_clock.jpg]

Today, time is measured with atomic precision. Cesium clocks define the modern second and govern GPS, telecommunications, and international finance. Human perception, on the other hand, oscillates between digital instantaneity and the search for slowness.

Conclusion: time, a mirror of societies

Image: Timeline

Credit: Wikimedia Commons (CC-BY-SA)

[https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File\:Timeline\_of\_Human\_History.svg]

Each civilization has shaped its vision of time according to its needs and beliefs. From Mesopotamia to atomic clocks, time is both a scientific instrument and a cultural reflection, a link between man and the universe, a rhythm imposed and felt.